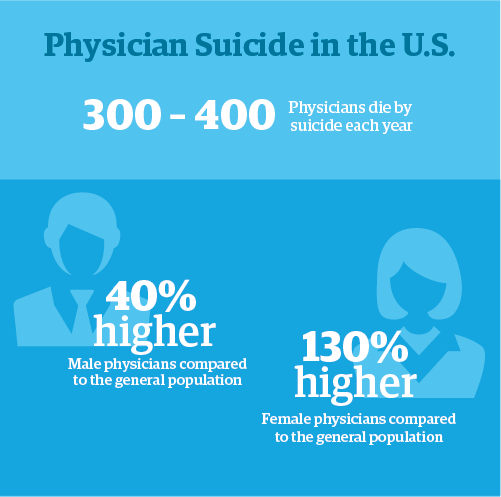

Suicide is a preventable tragedy, and all too often, it’s the outcome of the stigma, shame, and silence associated with mental illness. In medicine, that stigma and silence comes at a high cost: 300 to 400 physicians die by suicide each year.

According to the 2022 Medscape National Physician Burnout & Suicide Report, on average 10% of physicians have had thoughts of suicide. In some specialties, that number is even higher: 13% of pathologists surveyed, for example, reported having suicidal thoughts. Other high-risk specialties include general surgery (12%), oncology (12%), and infectious diseases (11%).

In light of this risk — which impacts physicians in every specialty — healthcare leaders have an obligation to understand and address the risk factors and root causes of physician suicide. More importantly, they have a responsibility to make it possible for physicians to get help without fearing for their careers.

7 risk factors for physician suicide

- Depression

- Emotional exhaustion

- Low self-valuation

- Untreated mental illness

- Substance abuse

- Marital status and impaired relationship

- Malpractice claims

Physicians have one of the highest rates of suicide of any profession; the rate for male physicians is up to 40% higher and for female physicians up to 130% higher than the general population. Seven of the most prominent risk factors for physician suicide are explored below. Other factors include age, general health, and access to lethal methods such as drugs or firearms.

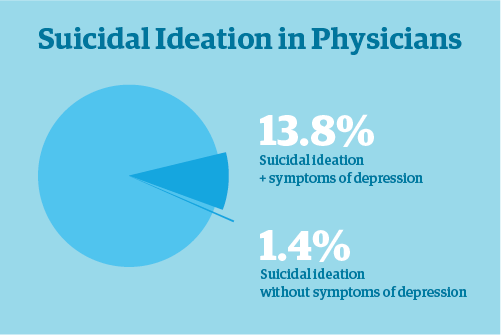

1. Depression

Depression is one of the most common factors associated with physician suicide; 13.8% of physicians with symptoms of depression reported suicidal ideation compared with just 1.4% of physicians without symptoms of depression.

2. Emotional exhaustion

Most physicians enter medicine because they want to help people. However, many suffer from unrealistic expectations, working long hours and worrying about their patients to the point of emotional distress and exhaustion. Although some studies suggest that burnout alone is not directly associated with greater suicidal ideation in physicians, burnout combined with depression was associated with greatly increased odds of suicidal ideation.

3. Low self-valuation

While physicians are known for their empathy and compassion toward other people, many are critical of their own imperfections and shortcomings. Described as low self-valuation, a tendency to self-deprecate can lead to lack of self-care and prevent physicians from seeking help. One study found that physicians in the lowest quartile of self-valuation had a much higher rate of suicidal ideation (15.1%) compared to those in the highest self-valuation quartile (1.7%).

4. Untreated mental illness

Mental illness is a key comorbidity for suicide. Postmortem toxicology data for physicians who committed suicide show low rates of medication treatment. One study of suicide victims found that physicians were significantly less likely than the general population to have antidepressants present at time of death. Physicians are also less likely to seek mental health services than the general population, which may be due to concerns for their career or a sense of greater self-resilience.

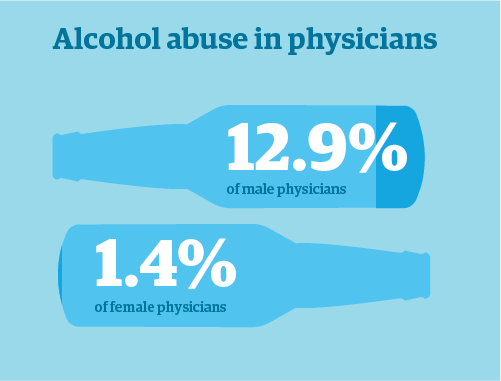

5. Substance abuse

The same toxicology study of suicide victims found physicians were more likely to have ingested substances such as antipsychotics, barbiturates, and benzodiazepine than the general population. Although abuse of prescription or illegal drug use is rare in physicians, up to 12.9% of male physicians and 21.4% of female physicians meet the diagnostic criteria for alcohol abuse or dependence, which is closely associated with depression and suicidal ideation.

6. Marital status and impaired relationship

The evidence is strong that marital status is a factor in physician suicide; the risk of suicide among divorced men in the U.S. is double that of married men. However, physician studies have conflicting data that suggests married or unmarried status can be either protective or detrimental, depending on the state of the relationship.

7. Malpractice claims

Physicians who believe they have made a major medical error in the past three months are three times more likely to have suicidal ideation. However, physicians who practice in specialties with a high occurrence of malpractice claims may experience less emotional distress than those in specialties where malpractice claims are not as common.

Download physician suicide risk factors as a PDF:

Unique risk factors in high-risk specialties

Some physician specialties come with unique stressors that can add to feelings of burnout and increase the risk of suicide. For instance, pathologists and infectious diseases physicians were subjected to additional stressors during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The pandemic increased stress for surgeons as well. First, surgeons faced the cancellation of elective surgeries, which greatly impacted their income. But once these procedures were able to resume, surgeons found themselves faced with a massive surgery backlog and pressure from financially strapped health systems to catch up.

“Surgery and surgical procedures really carry the bottom line for a lot of health systems, so there’s an intense pressure to catch up,” says Kathleen McCann, assistant director of member services for the American College of Surgeons. “With limited resources and a punishing schedule, that really impacts burnout.”

Dr. Amy Vinson, assistant professor of anesthesia at Boston Children’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School, and chair of the Committee on Physician Wellbeing for the American Society of Anesthesiologists, says anesthesiologists are often at the epicenter when it comes to high pressure situations.

“Obviously, we want things to go perfectly for our patients all the time — every doctor does — but that’s just not going to happen. Bad things are going to happen, sometimes within our control and sometimes completely outside of our control,” Dr. Vinson says. “But if anything goes wrong, we frequently carry the blame.”

Stigma and stereotypes

Physicians are expected to be immune to stress and mental health challenges, says Dr. Vinson. “But physicians — and other healthcare workers for that matter — are human. We can experience mental illness just as we can experience physical illness.”

“For physicians, there is an incredible stigma associated with seeking help for mental health and saying you’re not okay,” says Dr. Debra Williams, emergency medicine physician, founder of Dr. Deb Leads, and former chair of the physician well-being committee for the American College of Emergency Physicians. “We are trained to be tough, resilient, superhuman, make no mistakes — so you don’t show emotion, you don’t cry, you don’t ask for help. We’ve all fallen into that trap.”

Dr. Williams says physicians tend to be high achievers and perfectionists. “So, we have those personality traits to begin with. And then when our mentors and attendings set that standard of, ‘you’re tough, you don’t cry, you don’t break down, you don’t ask for help, you just do it,’ that has all, over the years, contributed to where we are now.”

That ingrained culture of quiet stoicism makes it crucial for healthcare leaders to focus on physician suicide awareness and address mental health openly and with compassion.

Making wellness work

Wellness programs are one tool to help physicians manage stress and burnout. However, all too often those programs are merely Band-Aids that offer simplistic solutions in the form of diet and exercise advice. Furthermore, “most expect you to participate on your own time doing activities you may not find recharging or refreshing at the expense of personal or family time that was already being impacted by your work after clinic,” says Dr. Margot Savoy, senior vice president of education for the American Academy of Family Physicians.

“If organizations want their wellness programs to be successful, they can start by asking what physicians find rewarding and helping them access that better,” Dr. Savoy says. “For example, creating easy access to mental health services like counseling and coaching, or thinking outside the box to create a better sense of community, can be successful strategies to engage your physician members.”

The American College of Surgeons has developed educational webinars that reframe well-being from a focus on yoga and meditation to the concept of moral injury. “One of the systems-level projects we’re working on right now is the Caring for the Caregiver program, which systems can implement within their surgical department so that surgeons know there’s a safe space and safe people to talk to about their issues and get support,” says McCann.

The need for systemic and local change

Over the past couple of decades, physicians have had to juggle greater and greater administrative burdens — and these tasks have become a major cause of burnout.

“In addition to the day-to-day emotional and cognitive burdens of delivering patient care, family doctors are often working second administrative jobs at night — entering data into the electronic medical record, completing prior authorization requests, returning patient calls/emails, and other paperwork related to practice,” Dr. Savoy says. Beyond feel-good recognition parties or after-hours wellness classes, physicians need “the practice support staff, tools, and resources to start and finish their work within reasonable working hours.”

Too often, physicians simply don’t feel supported in their workplace. Dr. Vinson routinely surveys her department about whether people feel supported and what they need to feel supported. “Then you can really tackle the microculture in your department by addressing those issues,” she says. “That’s really the most important question: ‘How supported do you feel in your work/life?’ We want to make sure that people feel supported in every aspect, in both their life and career.”

The career conundrum: Is seeking help worth the risk?

The hard reality for physicians is that the simple act of seeking help could jeopardize their ability to practice. State licensing boards and credentialing applications generally require disclosure of mental health diagnoses or treatment.

“As long as you can lose your career by seeking mental health care, there will be physicians who will not seek care until they are forced to by crisis,” Dr. Savoy says. “If we want to support our physicians, we must begin by protecting them and allowing them safe spaces to receive care without retribution or punishment.”

Dr. Vinson suggests licensure and credentialing applications treat mental health the same way they treat physical health. “So instead of asking, ‘Have you ever had a mental healthcare condition or diagnosis?’ and ‘Do you currently have any physical conditions that impair your ability to care for patients?’ We get that parity, and we ask them, ‘Do you currently have any mental or physical conditions that impair your ability to care for patients?’”

If healthcare leaders truly want to begin addressing root causes of physician suicide, they need to ask themselves, “What is it about the culture of medicine that leaves such successful, bright people in such an unsupported state?” Dr. Vinson says. “We can’t shrink away from asking the hard questions about what’s going on in our own house, even questioning some pretty central areas of medical culture.”

“We need to be talking about this more — opening a space where people can feel empowered to both seek help and talk about struggles,” Dr. Vinson adds. “But in order to do that, we need to do the heavy lifting as leaders to support legislative changes that address the conditions that created those barriers in the first place.”

Additional physician suicide support and resources:

- Physician Support Line: 1-888-409-0141

- Identifying and responding to suicide risk (AMA educational toolkit)

- American Foundation for Suicide Prevention (resources page)

- National Physician Suicide Awareness Day (Sept. 17)